THE FOREX TRENDS

Revealing the World of Forex: Expert Analysis and Secrets of successful trading

The year 2024 has been challenging for economic forecasters and monetary policymakers. Despite significant progress in 2023 towards the Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) price-stability goal, inflation surged in the first quarter of 2024. Meanwhile, the labor market and economic growth were robust, leading some to question whether the current monetary policy was sufficiently restrictive and if rate hikes should be reconsidered. These economic data fluctuations have shifted expectations about when the FOMC might start lowering its policy interest rate and the extent of potential cuts this year. Throughout this period, my consistent view has been that there is no immediate need to cut rates until the Committee is confident that inflation is sustainably returning to 2 percent.

In the second quarter, inflation and labor market data moderated, suggesting renewed progress toward price stability. Recent data indicate that the economy is growing at a more moderate pace, with labor supply and demand appearing balanced and inflation decelerating from earlier this year. These developments support the FOMC's dual-mandate goals. I believe current data points toward a potential soft landing, and I will closely monitor upcoming data to reinforce this view. While we have not yet reached our ultimate goal, we are approaching the point where a policy rate cut may be justified.

Before discussing the economic outlook, I want to touch on central bank communication, particularly regarding the policy path. Central bankers aim to clearly communicate progress and the remaining journey towards the ultimate goal. The challenge is that there may be multiple paths to that goal, depending on incoming data. For example, when commuting home, you might have a usual route, but traffic conditions might require an alternative path. Similarly, central bankers must consider alternative policy routes if the data deviates from expectations. It is crucial to communicate these alternative paths to the public, enabling them to plan accordingly. After reviewing the economic outlook, I will explore three potential inflation scenarios for the second half of 2024 and how they could influence my policy stance.

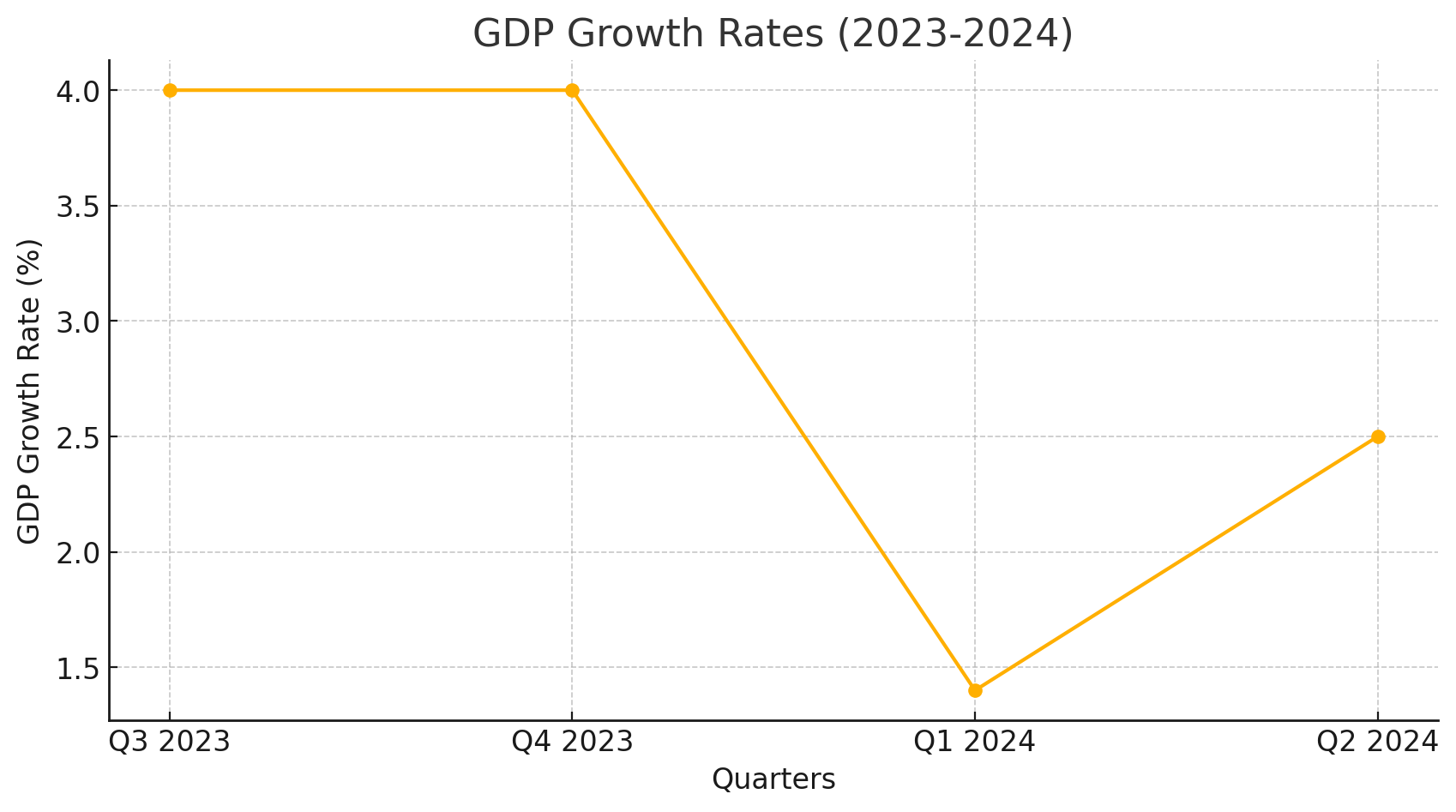

Let's begin with the economic outlook. Real gross domestic product (GDP) grew at about a 4 percent annual rate in the latter half of 2023 but slowed significantly to 1.4 percent in the first quarter of 2024. Forecasts suggest output grew slightly faster in the second quarter. We will receive an initial estimate of second-quarter GDP next week, but the Blue Chip average of private-sector forecasts estimates GDP growth at 1.8 percent, while the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow model predicts 2.5 percent growth. The higher GDPNow estimate is influenced by an updated retail sales report, showing solid gains in consumer spending data for June, with revisions for April and May also trending upward. This moderate consumption growth may continue in the second half of the year due to stable personal income data.

A potential indicator of slowing economic activity is the Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) survey of purchasing managers for non-manufacturing firms. Non-manufacturing firms represent a significant portion of the economy. In June, the non-manufacturing index fell below 50, suggesting a contraction in activity. The "business activity" index, which corresponds to production or sales, also dropped below 50 for the first time since May 2020. The new orders index fell sharply, and the employment index moved further into contraction. This data indicates a slowdown among these businesses, but the extent is uncertain. Previous instances of the index falling below 50 were followed by sustained periods above that threshold, so we need to wait to see the implications for this sector. Meanwhile, activity among manufacturing businesses has been relatively stable this year after contracting from late 2022 through 2023, with new orders and other readings close to 50.

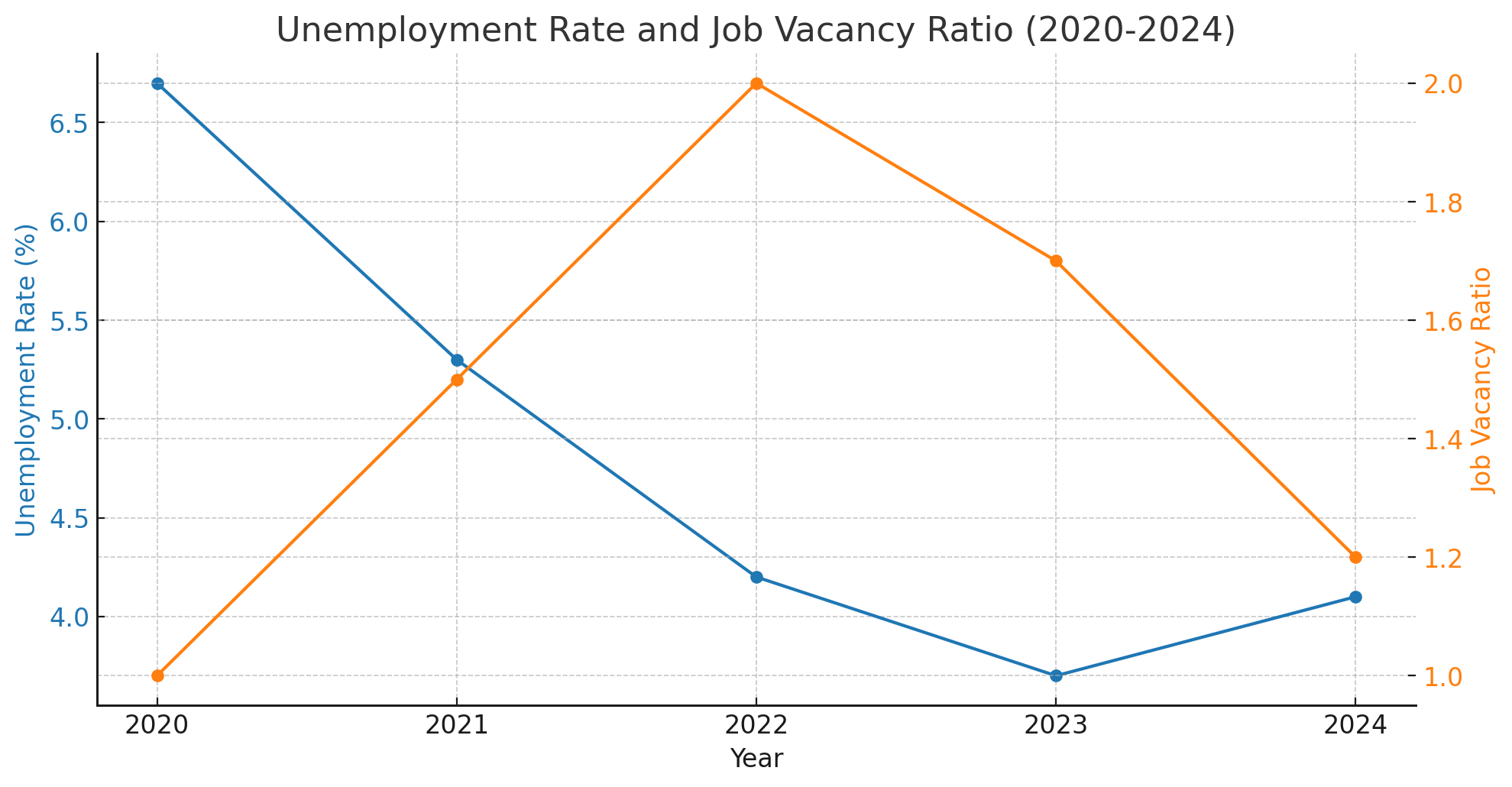

In recent months, labor supply and demand have achieved a rough balance, significantly impacting monetary policy. The demand for workers exceeded supply for several years, leading to high wage inflation and contributing to services inflation. The pandemic disrupted labor supply as many people left the workforce to care for family, older workers retired, and immigration decreased. Simultaneously, solid economic growth increased labor demand. This imbalance resulted in a surge in job openings, with nearly two vacant jobs for every job seeker, almost double the pre-pandemic rate. There was also a significant rise in the number of people quitting jobs, often to take higher-paying positions elsewhere.

However, this situation has now changed. Labor supply has improved with higher labor force participation rates and increased immigration. Previously, I would have been concerned that high job creation rates were inconsistent with a balanced labor market, but recent high immigration rates have accommodated strong demand. Additionally, as restrictive monetary policy has applied downward pressure on aggregate demand, labor demand has moderated.

The unemployment rate has risen from a 50-year low to 4.1 percent, still low by historical standards but the highest since late 2021. In May, the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed people was 1.2, which was the average before the pandemic. The share of workers quitting jobs is now slightly below pre-pandemic levels. One sign of a loosening labor market is that layoff rates have remained steady at around 1 percent. This data suggests that labor supply and demand are balanced.

In 2022, I co-authored a research note with Fed economist Andrew Figura on the Beveridge curve, the relationship between unemployment and the job vacancy rate. We projected that, if layoffs remained steady, the unemployment rate would rise to around 4.5 percent if the job vacancy rate returned to its pre-pandemic level of 4.6 percent. The latest data estimates the vacancy rate in May at 4.9 percent, close to pre-pandemic levels. Despite some skepticism, this data suggests that if inflation continues to moderate, we may achieve a soft landing in the labor market with minimal unemployment tradeoff.

Wage growth has also slowed. The 12-month change in average hourly earnings decreased from about 6 percent in March 2022 to 3.9 percent in June 2024. The three-month increase through June was running at an annual pace of 3.6 percent, close to the rate needed to support 2 percent inflation sustainably. Other measures also suggest that wage growth has returned to pre-pandemic levels.

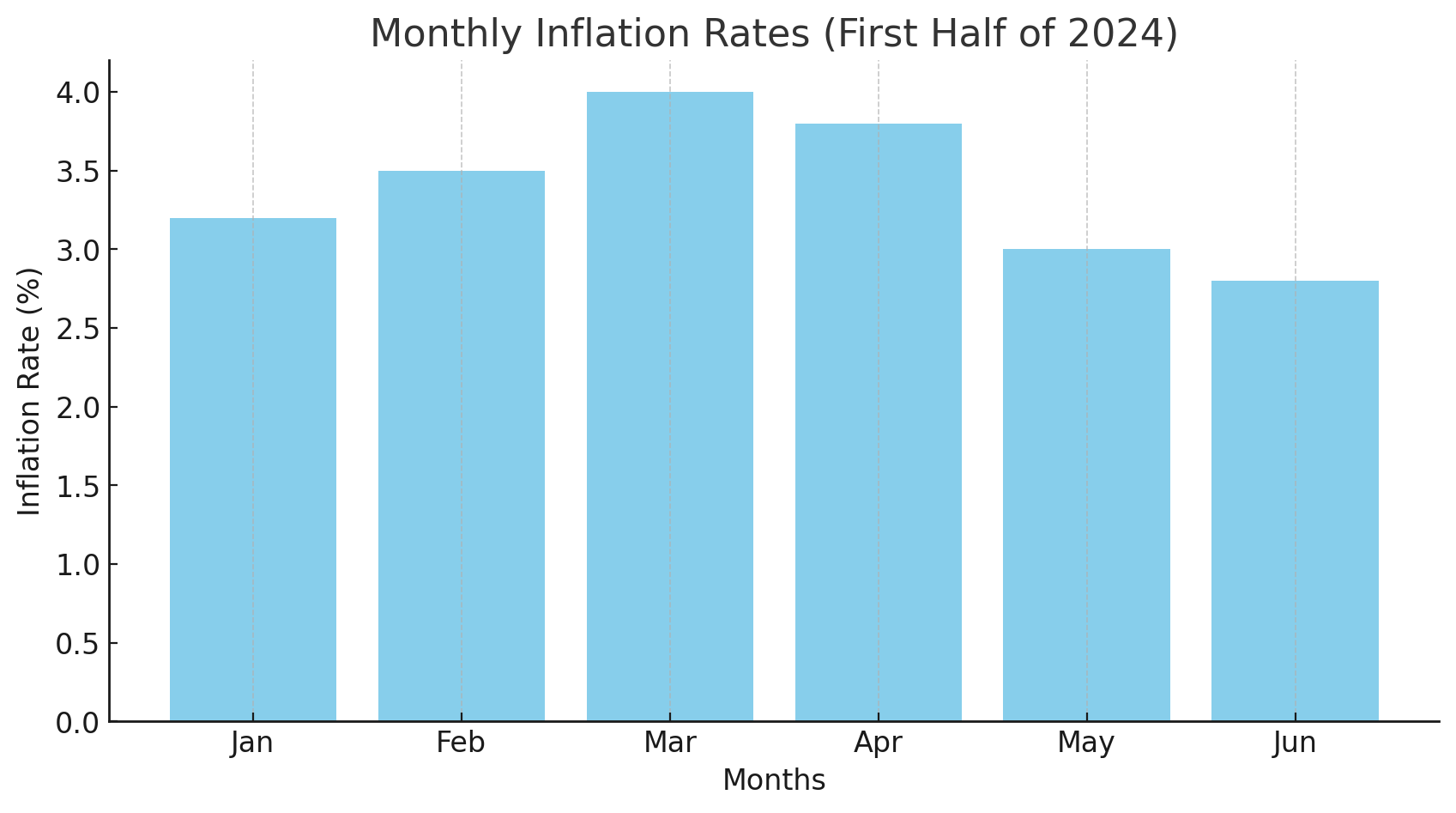

Turning to inflation, after making progress toward our 2 percent goal last year, I was concerned earlier this year that progress had stalled. However, recent data has been reassuring. Last week's consumer price index (CPI) report marked the second month of very positive news. It showed that total consumer prices fell in June, following a flat reading in May. This brought CPI inflation for the 12 months through June down to 3 percent, with a 3-month annualized change dropping to 1.1 percent. For consumers, who have faced significantly higher prices since the pandemic, this is encouraging news. With solid gains in wages and other income, we hope it will feel like prices are becoming more manageable over time.

For policymakers, this was also welcome news. Excluding energy and food prices, which are often volatile, core CPI inflation rose by only 0.1 percent last month, the slowest pace since the pandemic. This brings the 3-month annualized core inflation rate down to 2.1 percent. Based on recent consumer and producer price data, private sector forecasters predict that the FOMC's preferred inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) index, rose 0.1 percent in June, with core PCE inflation increasing by 0.2 percent.

After a disappointing start to 2024, recent data aligns more with the steady progress seen last year in reducing inflation and supports the FOMC's price stability goal. The evidence suggests that the first-quarter inflation spike may have been an anomaly and that tighter monetary policy is effectively containing high inflation. Over the past 18 months, core PCE inflation averaged 0.4 percent per month in the first quarter of 2023, then decreased to 0.3 percent, 0.2 percent, and 0.1 percent in subsequent quarters. Core PCE inflation jumped to a 0.4 percent monthly average in the first quarter of this year but is now estimated to be back at 0.2 percent last quarter. This recent data increases my confidence that we will achieve our dual mandate's inflation goal.

Now, let's discuss the implications of this data for monetary policy. The changing data this year has made it challenging to formulate a consistent policy outlook. We must consider two risks: loosening policy too soon and allowing inflation to rise again, potentially losing public credibility, and waiting too long to ease policy, risking a significant economic slowdown or recession.

With these risks in mind, I present three scenarios for the economy this year, each leading to different policy views. One assumption is that the labor market remains stable, without significant deterioration in the coming months.

These scenarios underscore the importance of data-dependent policy decisions. While I remain optimistic that the first two scenarios are most likely, signaling a possible rate cut in the near future, we must remain vigilant and adaptable to changing economic conditions.

In conclusion, my views on the appropriate policy path will continue to evolve with incoming data, ensuring we effectively balance our dual mandate of price stability and employment.

Stay updated with the latest developments on U.S. inflation by following our website. If you have any questions or suggestions, feel free to contact us or leave a comment below.

For more detailed information, you can access the full speech at the Federal Reserve's official website.

Comments